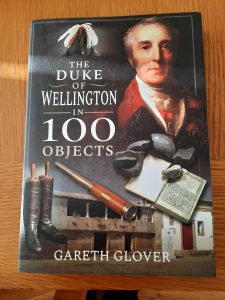

Published by Frontline Books October 2020

Published by Frontline Books October 2020

This is the second volume of a pair meant to be published in 2019, to mark the 250th anniversary of two of the greatest men in world history. Both Napoleon Bonaparte and his greatest adversary, Arthur Welsey (later Wellesley), the Duke of Wellington, were born in the remarkable year of 1769. When I say remarkable, I do not mean because of particular world events, scientific discoveries or even life-changing social revolutions. What 1769 should be famous for, is the incredible number of military men born this year, many of whom would certainly appear in a list of the world’s top one hundred military leaders of all time. Beyond Napoleon and Wellington, 1769 saw the birth of Marshals Ney, Soult, and Lannes, Generals Decaen, Anson, Lumley, Arakcheyev, Malcolm, Belliard, Brock, Muhamad Ali, von Decken, Hope, Joubert, Markov, Thiebault, Wallmoden and Wittgenstein, not to mention Admiral Hardy (of ‘Kiss me Hardy’ fame), Sir Hudson Lowe (Napoleon’s gaoler) and Sergeant Ewart (who captured an eagle at Waterloo), to name but a few. In fact, well over fifty major military figures were born this year, a truly remarkable total.

Arthur, Duke of Wellington did not become an emperor or a king, but in every other respect, his influence throughout Europe was just as great as Napoleon’s. His renown was great before the Battle of Waterloo, but after his great victory, ably assisted by Marshal Blucher, he was feted everywhere as ‘the conqueror of the conqueror of Europe’. After that stunning success, he could not walk into any function anywhere, without the band striking up the tune to the hymn ‘See the Conquering her comes’.

There however, almost all the similarities with Napoleon Bonaparte end, their characters, backgrounds and careers being very different and fate only ever brought them together, to meet across a battlefield on 18 June 1815.

Arthur Welsey (the family later changed the spelling to Wellesley), was born into minor aristocracy in Ireland and he did not show any great aptitude for anything, apart from playing his violin quite well. With his father dying whilst young, he went into the army, and rose in rank quickly thanks to his brother’s financial support. However, the British Army he joined was at a low ebb and as he said himself, his early forays abroad taught him the valuable lessons of how not to do things. Arthur showed some early promise as a soldier, but he had yet to commit himself to the profession and he enjoyed a wayward life, which drew much criticism from friends and family. Unrequited love was to change all of this, for having fallen head over heels with the beautiful Kitty Pakenham, he sought her hand in marriage, but was refused by her family, as having no fortune and few prospects of ever attaining one. Being spurned, was the turning point in Arthur’s career, as he determined to make a serious effort to gain promotion and success within the army, so that he could return to finally gain Kitty’s hand in marriage.

Arthur was sent to India with his regiment, where his elder brother was already installed as Governor General. This gave him the opportunity to command large armies of British and native Indian troops in government regiments and also work in coordination with various Indian princes with whom the British were allied. The experiences of marching through thick jungle, carrying everything needed in the way of supplies with them and engaging huge armies of ill disciplined Indian troops with much smaller armies of highly disciplined soldiers using European methods, saw him win some incredible victories, such as the Battle of Assaye and the storming of Gawilghur Fortress. Returning home in 1805, the victor of numerous battles in India and more importantly, rich, he now gained the hand of Kitty and his military career continued to burgeon.

Wellesley’s great opportunity would come on the European stage, with Napoleon’s ill-fated decision to invade Portugal and then to usurp the crown of Spain and give it to his brother. The British had a small army, but a huge navy which had already gained virtual control of the oceans and British manufacturing and trade, meant that Britain had very deep pockets indeed. Whilst heavily subsidising Napoleon’s enemies, Arthur was sent with a small British army into Portugal and he quite quickly gained a high reputation, having defeated French armies in the field, something that was almost unknown in Europe these last ten years.

Wellington’s organisational skills, strategic expertise and superb abilities in close command slowly moulded his British army into a superb fighting force, whilst he also saw the Portuguese army brought up to the same standards and eventually became Commander in Chief of the Spanish forces as well. Despite never being able to put anywhere near comparative forces within the field, he fought in the peninsula for six years, eventually driving the French out and even pushing his forces deep into Southern France, before Napoleon was forced to abdicate. Napoleon’s overthrow was not down to Wellington alone, as Prussia, Austria and Russia fully participated in finally bringing him down, but Wellington’s stunning victories often gave hope at a time when Napoleon was routinely crushing any opposition to his ambitions in central Europe.

Wellington gained great honours and riches from all of the allied sovereigns and he was sent to the Congress of Vienna to use his undoubted influence to gain concessions, particularly relating to Britain’s attempts to garner support for the end of the slave trade.

However, his fame following his stunning victory at Waterloo eclipsed all that came before and he became one of the most famous individuals in the entire world and he was invited to almost everything. He was given command of the entire combined European army based in France for three years to oversee the re-establishment of Royalist France, whilst Napoleon was banished to St Helena, where he saw out the rest of his life.

With the war finally over (Britain had been at war almost continuously for twenty-three years), Arthur was taken into the British cabinet and he soon became a leading politician and eventually became Prime Minister in 1828 and saw through the Catholic Emancipation Act and helped to see the Great Reform Act through, although he was not sure about it. His political career was however, not as dazzling as his military career, but he was able to exert enormous influence on people and events and did so always in the belief that what he did, he did for the best for his country. He was always loyal to his sovereign and he was close to all three that reigned after he came home from the wars.

When he finally died in 1852, the entire country went into mourning and his funeral procession was one of the largest ever seen in Britain, with over one and a half million crowding the streets to glimpse the coffin as it passed.

Like every great, larger than life character, the legacy of the Duke of Wellington is huge but not everything he did is regarded well today and opinions are divided. As a historian I have attempted to take an impartial balanced approach in describing the various aspects of his life and I leave it to the reader to make their own final judgement on him.

Arthur Wellesley was never a tyrant, indeed when the opportunity arrived to possibly be one, it never occurred to him to take it. Duty was his simple watch word. Duty to his monarch, duty to the country and duty to his family and he often went against his better judgement in support of these simple principles. A caricature of the man has developed over the centuries, as that of a hard, indeed heartless man, who was cold and aloof, and a reactionary who refused to move with the times. Like all such simple stereotypes there is an element of truth in them, but there is a great deal of evidence that shows a man who demanded much from his subordinates, but cared greatly for their welfare, he often showed great remorse and was actually seen to break down and cry on a number of occasions, where his orders had led to the deaths of large numbers of his troops, he was also passionate and often to be seen walking with the lowest in society and happy to be alone in their company. His political career has often been criticised, but he tempered his zeal for the status quo, by being pragmatic and bending when the winds of change were simply too strong to avoid being broken. By the end of his life he was feted as a truly great man and he is recognised as having had a greater effect on Britain in the last two centuries than anyone, perhaps with the exception of Winston Churchill. Today, he is seen as a lesser figure within Europe but at the time nobody eclipsed him, he was a true giant on the world stage.

How he rates alongside Napoleon, only the reader can decide, having viewed the achievements and failures of both, but have no doubt, that in the early decades of the nineteenth century, these two men were seen as two equal giants on the world stage.

It has been my honour to bring both of their superb legacies into perspective over these two volumes.