Available from

Ken Trotman Books

As I travel the country for various Napoleonic events, I often meet people who have incredibly interesting possessions, either from family or obtained from auctions. Recently, at an event in Winchester, I was lucky enough to meet with Paul Morrison, who soon informed me that a number of years ago he had purchased an item at a local auction house, which he thought might be of interest.

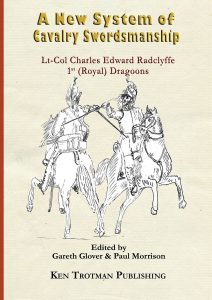

Having exchanged contact details, one week later I received a booklet in the post, a beautiful photographic reproduction of an original hand-written text which Paul proudly owns. The beautiful written text was immediately of interest, having been written by an ex Peninsula and Waterloo veteran. But of far greater interest, was the discovery of a large number of beautifully drawn pen and ink diagrams to illustrate the text, showing clearly both contemporary uniforms, and the standard sword movements.

Having realised the importance of the work – being ‘improved’ sword exercises suggested by a cavalry expert, who had seen the old system fail in the peninsular war. It is stated that his new system was used with great success at the end of that war and at Waterloo. Interestingly, the most obvious amendment he introduced with great success is one that is never associated with British cavalry swordsmanship of this period, namely the stabbing movement with the point or ‘lunge’. Because the 1796 British heavy cavalry sword used during these wars were designed as a ’slashing’ or cutting sword, it is presumed that the British never used them for stabbing.

This newly discovered first-hand evidence, from a very experienced officer, would seem to prove this as a fallacy. This would also tie in with the evidence we do have that the heavy cavalry ground their swords to a point before the battle.

Charles Edward Radclyffe, although from minor landed gentry, would appear to have joined the army as a private soldier in the 1st (Royal) Dragoons in 1793 and he first served under the Duke of York in the campaign of 1794 in Holland. He became the regimental adjutant on 25 June 1796 when still a sergeant and gained his commission as a cornet on 12 April 1799, before becoming a lieutenant on 4 May 1800, and a captain on 1 December 1804.

He embarked for the peninsula with the Royals in September 1809, and on taking the field in the ensuing spring, he was selected by Lord Hill to occupy with his troops a post of some difficulty and hazard near Elvas; and thence to make a reconnaissance across the Guadiana; he was subsequently employed on similar duties under the Quarter Master General of the army. In June 1810, he was appointed Major of Brigade to General Slade’s brigade, which consisted at that time of the Royals and the 14th Light Dragoons. He continued in this position throughout the war, up to the Battle of Toulouse in 1814, without a day’s absence, except on two occasions of dangerous attacks of fever, brought on by the fatigue incident to the duties of his situation. was present at the battles of Salamanca, Vitoria, Busaco, Fuentes d’Onoro, the blockade of Pamplona and the attack on Bayonne, besides numerous engagements of minor note in which the cavalry was concerned; he acted twice as Deputy Judge Advocate to the general court martial in the cavalry.

In the action at Maquilla on 11 June 1812, in which Slade’s Brigade (Royals and 3rd Dragoon Guards) was worsted by General Lallemand and driven in confusion for six miles with a loss of 150 men, Slade reported that he was particularly indebted to Radclyffe for his assistance in rallying the men.

Whilst serving with his corps, he submitted to its General Slade the result of his observation and experience on the use of the sword in the hand of a heavy cavalry soldier, urging the necessity of the application of the point so much more efficient than any cut, however powerfully given: and under his direction gave instruction to the men in the thrusts, ‘quarte and tierce’; he had afterwards the satisfaction to see this idea taken up and enforced by the highest cavalry authorities; and the tremendous execution of this arm, so applied at Waterloo, fully justified the adoption of the principle.

Radclyffe was employed as the Assistant Adjutant General of the cavalry during the march of all the cavalry across France after the war and in that situation, he attended the reviews of the several brigades and regiments before the Prince Regent, on their return to England. He received a brevet majority on 4 June 1814, and on 25 September was made Brigade-Major to the Inspector General of cavalry, Sir Henry Fane.

On the renewal of the war in 1815, the Royals were ordered to France, he therefore gave up his Staff appointment, and went to Belgium with his regiment, which formed part of the famous Union Brigade. His squadron constituted the rearguard of the brigade in the retreat from Quatre Bras on 17 June, at Genappe it was singly opposed to two squadrons of Chasseurs a Cheval and some light infantry; and he was thanked for his conduct by Sir William Ponsonby. He was specially praised also by Ponsonby’s successor, Colonel Clifton, for his part in the great cavalry charge at Waterloo on the following day. He was severely wounded by a bullet in the knee, which could not be extracted, and which caused him much pain for the rest of his life. He was given a brevet lieutenant-colonelcy, dating from the day of the battle.

Parliament approved a pension for him in 1816

1st Dragoons Captain Charles Edward Radclyffe For a wound Waterloo £100

As a result of his experience in the war, Radclyffe submitted a strong recommendation that British troopers should be taught to use the point instead of the edge of their sabres and published a small work on the subject in 1818. No copy of this book has been discovered in any library in the world, but the original hand-written original has now been found and is published here for the very first time.

He was placed on half-pay on 20 April 1820 and he died in London on 24 February 1827. ‘He was a dexterous swordsman, an accomplished officer, and an able tactician … a warm and sincere friend, a conscientious Christian, and a brave man,’ wrote General de Ainslie, the historian of the Royals.

He married Mary, eldest daughter of Mr H. Crockett, esq. of Littleton Hall, on 5 March 1800 at St Editha, Church Eaton in Staffordshire and who died only a few days before him and are recorded alongside each other in the burial record of Holy Innocents Church on Kingsbury Road in London on 28 February 1827.

Their only son, christened Charles Edward Radclyffe at Church Eaton on 3 September 1801, became a clergyman and died in 1862, leaving an only son, Charles Edward Radclyffe, of Little Park, Hampshire.

Charles Edward Radclyffe was the son of Edward Radclyffe of Barnsley (born in 1728) and Elizabeth Adamson (his second wife, who he married in 1768).

His siblings were:

Anne Radclyffe (a step-sister, being born to his father’s first wife Anne Ellis who died in 1767) who later married a William Jackson of Barnsley

William Radclyffe, born in 1770, he married Elizabeth Marechale in 1804 and had issue

Thomas Radclyffe, who married Philadelphia Whaley in 1797 but died without issue

Our Charles was born in 1774.

Elizabeth Radclyffe, who later married John Salway of Richards Castle

Their father married a third time, to a Sarah Hall on 20 July 1797, but had no further issue