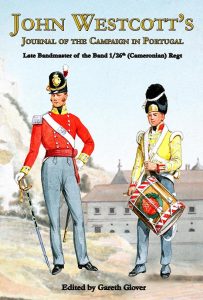

John Westcott’s Journal of the Campaign in Portugal, Late Bandmaster 1/26th (Cameronian) Regiment

Available from Ken Trotman Ltd

This handwritten journal has lain in the British Library for well over a century, largely ignored, which is a great shame. We actually know very little about John Westcott as his service papers do not seem to have survived, but it would appear that his father may well have been born in Plymouth, serving in the 33rd Foot and the 3rd Foot as a Sergeant and eventually joining the 26th Foot (the Cameronians) before retiring on a Kilmainham pension in 1792. It would seem that although he was treated as a member of the regiment, that in fact he was a supernumerary as he does not appear in any of the monthly returns of the battalion. But for all our lack of knowledge of the man, the same cannot be said of his writings. The 1st Battalion 26th (Cameronians) had served the early years of the Revolutionary wars in Canada, only returning home in September 1800. They were soon off to warmer climes, serving in Egypt in 1801 and returning to Britain in 1802. The regiment was then stationed in numerous garrison towns throughout Scotland and then Ireland, where in 1804 a second battalion was raised. In late 1805 the 1st battalion was sent to Germany, but tragedy struck when two of their transports were wrecked in gales and 488 men 52 women and children were lost. The remnants returned to England in early 1806 and then marched to Ireland to receive over four hundred drafts from the 2nd battalion. In October 1808, the 1st battalion was sent to Spain but arrived only in time to take part in the terrible retreat to Corunna. In 1809 the battalion received two hundred men from the 2nd battalion and a large number of recruits from the Lanarkshire Militia, only to be sent off immediately to Walcheren where Westcott appears to have joined them, as he mentions this campaign a few times.

At the beginning of 1810, we find the battalion at Horsham with only ninety men fit to do duty, the rest being in hospital with a form of malaria contracted on the pestilential island of Walcheren. This fever was to follow them to Spain a year later and would ravage them again. They were then stationed at Grouville Barracks in Jersey from 14 June 1810 until June 1811.

The 1st battalion then sailed for Portugal, where it arrived after a very pleasant and speedy voyage on 4 July. The battalion soon landed and were quartered in a convent at Lisbon, to give them time to recuperate before they marched to join Wellington’s army on the north-western borders of Portugal. However, following the Walcheren expedition, the regiment suffered from a continuous stream of personnel falling sick with fevers and many of the men unable to endure long marches or great physical demands. After only a year in the Peninsular, the constant sickness forced Wellington to order their departure to Gibraltar, releasing other troops from that garrison for his use.

John Westcott, as a Band Master, would not have expected to see much fighting, but the Cameronians saw no fighting during their period in the Peninsular anyway, although some fighting did occur in their vicinity. They were present near the action of El Bodon although not engaged and were unfortunately deemed too sickly to proceed with the army to the siege of Ciudad Rodrigo.

This lack of battles does not mean however that his memoir is not a treasure trove for the student of the British army in the Peninsular war. Westcott talks a great deal about the country of Portugal and its people and openly avows their worth as soldiers. He notes in great detail the Portuguese units he encounters, the French prisoners of war (including General Philippon at Lisbon Castle), and even identifying their individual regiments; he tours the hospitals for the army and describes fully the terrible conditions and depravations the army had to endure. He visits the scene of the Battle of Bussaco one year on and the fortress of Almeida following the truly awful explosion there and in both cases, he portrays the remains of these events in lurid detail. Indeed, military historians often complain that the soldiers do not mention the regular and to them the mundane, making it difficult to fully understand their plight. The joy of this book is that it helps significantly to fill a great number of these blanks in our knowledge and is therefore highly recommended for anyone who really wants to understand Wellington’s army.