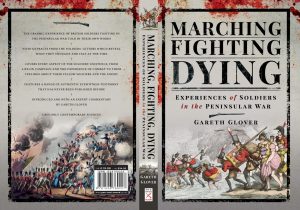

Published by Pen & Sword December 2021

A huge number of books have been published over the last two centuries on Wellington’s army during the seven-year campaign in the Iberian Peninsula. Some of these works have been ground-breaking, utilizing significant original archival research to produce in-depth analysis which challenges our preconceptions and long-held beliefs. Unfortunately, however, these are still quite rare, while far too

many simply repackage and regurgitate the same tired old clichés and use the same tried and trusted published sources, bringing little more to our understanding.

Many of these volumes have understandably concentrated on the strategies used (both at high and low level), the political maelstrom the war engendered and, of course, in-depth analysis of all of the individual campaigns, battles and sieges. Alongside these, there have also been a plethora of titles dealing with the uniforms worn and equipment used by the different armies, the logistical problems

encountered in feeding large armies in the peninsula and even the influence of sea power on the campaign.

One aspect regularly explored within such works, is the analysis of the life of an ordinary soldier during these extremely hard campaigns. Previous titles on this particular subject, include Charles Oman’s Wellington’s Army 1809-14, Antony Brett-James’ Life in Wellington’s Army, Colonel H.C.B. Rogers’ Wellington’s Army and of course Edward Coss’s All for the King’s Shilling: The British Soldier

under Wellington 1808-1814, to the very latest, in Gavin Daly’s The British Soldier in the Peninsular War.

Alongside these works, many general histories of the campaigns and specific regimental studies often dip their toe into this subject area, as part of their overview of the campaign, but are usually little more than

derivatives of these major works. However, all of these worthy titles often suffer from the same single major flaw and it is the specific intention of the present volume to right this serious error.

There is an erroneous belief that literacy rates in Britain were very low in the early decades of the nineteenth century. In fact, literacy rates in Britain between 1750 and the early 1800s remained pretty constant at some 53 per cent of the adult population, but this generalized figure hides the true picture.

In fact, male literacy rates regularly hovered around 60 per cent, whilst women saw a slow rise from a low of 30 per cent up to 40 per cent during this period and the gender gap continued to shrink until the 1880s, when it finally closed with both genders seeing literacy rates into the high 80 per cents.

It is also presumed that both the Army and Navy were generally filled from the very lowest strata of society and therefore literacy rates were markedly lower within the armed forces than in the general population. There may well be a grain of truth in this assertion, but it can be shown that literacy rates within the armed forces was not as low as many would have us believe. The notion that the Army was simply full of the dregs of society and that very few in the ranks were literate is not only an outdated assertion, but is demonstrably wrong, although it is still strongly believed by many to this day. In fact, only around 5 per cent of recruits failed to sign their form (marking with an X instead) or record a

previous trade of any description, although the ‘catch-all’ profession of labourer, which accounted for around 40 per cent of recruits, would clearly include a large number of unskilled workers, particularly agricultural labourers, with a low educational and literacy attainment. However, as the war progressed and economic hardships bit harder, the number of recruits from trades, particularly weavers from the hard-hit textile trade (hand weavers in Stockport saw wages decline from 25 shillings per week in 1802 to only 10 shillings in 1811), grew very significantly and therefore the educational standards of the average recruit rose with it.

A second, but significant factor in the steady rise in levels of literacy in the Army, was the rise of religious Nonconformism, believing in individual Bible study, which of course encouraged converts to become more literate. Many senior officers, including the Duke of Wellington, were initially wary of the

steadily-increasing number of prayer meetings and Bible study groups which were sprouting up within the Army, based on the fear that these soldiers would be less inclined to fight. However, experience showed this to be a fallacy and Wellington allowed them to continue, although it is undoubtedly true that officers were strongly discouraged from becoming involved.

This steady increase in overall literacy levels becomes significant during the 23 years of global war that was fought from 1793 almost without intermission until 1815, because of the very significant rise in the number of letters, journals and memoirs available to the researcher. The volume of social correspondence noticeably increases with each year of the war, but not simply within the better educated officer class and non-commissioned officers, who were required to be literate to carry out their role fully, including completing written returns.

There is also an admittedly smaller, but rapidly increasing, volume of personal correspondence from ordinary rankers as the war progresses and more is undoubtedly yet to be unearthed, as all the available archives are still yet to be searched thoroughly.

Even while the war continued, a few sets of letters were published from individuals serving in the Army, whilst journal-keeping on campaign almost became the height of fashion for officers. This however was less common for non-commissioned officers and virtually unknown for those in the ranks.

However, after the ‘Great War’ – as the Napoleonic Wars were known to Victorian Britain – there grew an insatiable public hunger, for reminiscences of soldiers who had fought in the war, which graphically described not only the valour and bravery of battle, but also the hardships of long marches under a

broiling sun and the terrible living conditions and hunger that they had often endured. Indeed, the genre is not unknown in our own times, with a public fascination still obvious for memoirs of those who fought in both World Wars and more modern conflicts.

This encouraged many ex-soldiers to dust off their old journals written during the conflict, or they simply wrote down whatever they could vaguely recall of events which happened decades before. However, such a competitive market, with its constant demands for ever-greater revelations, forced them to seek to bring more excitement to their stories. Unfortunately, the experience of

war for most people is truly stated as ‘long periods of boredom punctuated by short moments of excitement’.

It therefore often forced them to look beyond their own often mundane experiences, utilizing stories and experiences shared around the campfires, simply plagiarized from other accounts and unfortunately

in some cases, completely invented. Indeed, commercial writers even went so far as to ‘ghost write’ completely fictitious accounts of the war, possibly with the aid of an old campaigner for that feel of authenticity and these have too often been accepted as factual accounts by unwary historians. Indeed, the use of the term ‘Adventures’ in their titles should always cause the historian to check their claims

thoroughly. These memoirs should therefore be treated as suspect and must be used with extreme caution, fully understanding that their trials and tribulations will be heightened for pathos and their descriptions of battles and sieges fully exploit the reader’s eager desire to read of valour, bravery and derring-do.

For all of these reasons, these memoirs are not firm material on which to base the true understanding of the soldier’s lot serving with Wellington’s army in the Iberian Peninsula. The dreaded ‘hindsight’, over-embellishment, exaggeration and the overt influence of William Napier’s beautifully described but extremely biased History of the Peninsular War make their accounts far too suspect to be of real use in gauging what it was really like to be there.

Even journals, apparently written up daily but not published until many years after the war, were susceptible to reworking by their authors. This again has to be guarded against, but the dangers of some editing of entries is less marked in those the author has studied, with many such journals produced purely for the interest of their families and themselves in later life. They were clearly never meant

to be published and have often only been brought into the public domain many decades or even centuries later by military historians, who have generally faithfully reproduced the originals verbatim. The libellous and disparaging descriptions of fellow officers, the highly critical comments regarding the leadership qualities of their senior officers and their open criticism of the actions and tactics of

their commanding generals prove that they were never intended for public scrutiny.

However, without doubt, the best evidence available to historians are the original letters sent from individual soldiers to their loved ones and the replies they received. The letters can contain much rumour and supposition, but no other writings honestly show the hopes, beliefs and aspirations of individuals at any given moment better than these. Secure from any fear of a censor and often

totally disregarding the danger of the letters falling into enemy hands, these letters allowed the correspondent to vent their spleen in anger and frustration or to discuss their cunning plans for gaining recognition and advancement and to extoll their own virtues, when no one else seemed to notice them. Much of what they say about the war, future operations and the abilities of senior officers were

clearly never meant to be discussed beyond the four walls of their family home and regular cautionary statements appear warning against breaking this rule, many a young officer finding his career prospects severely blighted by the publication of their letters home in the newspapers, which were regularly delivered to the Army with the post.

This, of course, was a time when every single aspect of life was contracted via copious paperwork – indeed life seems to have consisted for many of little more than reading and writing endless reams of correspondence. Everything was committed to paper in a society which was influenced, instructed and indeed was completely reliant on the written word to function at all. Postal services were

therefore highly efficient for the age, although overseas mail was always very susceptible to the vagaries of the winds and the threat of capture by enemy ships.

Indeed, the Post Office packets ran out of Falmouth regularly, once a week to Lisbon, while another sailed weekly for La Corunna (later in the war this changed to San Sebastian). In perfect wind conditions this journey could be achieved in four to five days, but in stormy weather or contrary winds this same journey could last up to three or four weeks. What it provided, however, was the possibility of a very regular and pretty certain correspondence with home and it was used increasingly to keep in touch with family and friends, to conduct business whilst out of the country and to obtain much needed supplies from Britain via parcel post.

All of this encouraged the regular two-way correspondence between members of the Army and family at home and it is this material, written for a private, trusted audience, full of their hopes, fears and the gossip of the Army at that precise moment, that is so vital to historians, enabling us to gauge their

honest, unfiltered views on all aspects of military life and the operations they were involved in at the very moment it was happening. It is for these reasons that the author has chosen to reappraise their

impressions, of the countries and peoples they encountered, the trials and tribulations they endured while serving in the British Army in such a trying climate and their attitudes to every aspect of this ‘alien’ world, only using their letters and the journals that can be shown to be untainted by later amendment

or manipulation. This decision purposely prohibits the use of any of the post war memoirs that flourished so much in Victorian times, but are so badly tainted as serious historic documents. Readers knowledgeable on the Napoleonic Wars will therefore search in vain for excerpts from such household names as John Aitchison, James Anton, George Bell, Robert Blakeney, Henry Browne, Edward Costello, Joseph Donaldson, George Gleig, George Hennel, James Hope, John Kincaid, William Lawrence, Jonathan Leach, Thomas Morris, David Robertson, August Schaumann, Moyle Sherer, George Simmons, Harry Smith, William Surtees, William Warre and William Wheeler. One later journal has, however, been utilized, this being the memoirs of Private John Morris Jones of the 39th Foot, for a limited number of passages where he deals with subjects rarely discussed in letters home.

Most of the correspondents utilized in this work will be completely unknown to the reader or at least little known, for far fewer of these much less exciting, but far more historically significant letters and daily journals have been published, something that the present author continues to seek to rectify.

The views and attitudes they portray are fresh and uncensored, but more importantly they are untainted by hindsight, revision or any of the other dreadful alterations and amendments that can seriously tarnish, if not completely destroy, their value as historic documents. Some of their attitudes will be familiar and will back up preconceptions based on reading the memoirs, but at other times, their

attitudes will surprise the reader and seriously challenge these preconceptions. All that can be said is that, this is the nearest we can ever hope to get to actually being there, over 200 years ago and experiencing what they saw and endured.