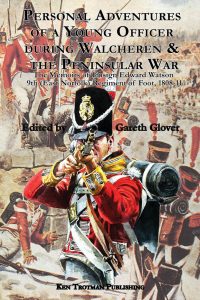

Memoirs of Ensign Edward Watson 9th (East Norfolk) Regiment of Foot

Available in softback from Ken Trotman

I discover the memoirs of soldiers of the Napoleonic Wars in many different ways and it is odd how the discovery of one often leads directly to others; this is one such case. Attending the archives at Norwich Castle to check through the letters of Lieutenant Colonel Sir John Cameron,[1] the archivist kindly provided me with a copy of another Napoleonic memoir they had a copy of. This unnamed religious journal printed in Norwich in the late 1850’s rather surprisingly contains the memoirs of Ensign Edward Watson of the 9th Foot, who served with the regiment from 10 August 1808, remaining throughout with the 1st Battalion, serving at Walcheren and in the Peninsular until he resigned his commission on 8 August 1811.

The Watson’s were a great military family, Edward’s great-grandfather being the first Lieutenant Colonel of the Royal Artillery Regiment when it was officially formed in 1716. Jonas had two sons, Lovegood and Justly, Edward’s father, another Jonas, being Lovegood’s seventh and last child, was born in 1748. His father had served with the 65th Foot and saw action at the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775 at the beginning of the American War of Independence. He then served as governor of Fort Niagara in Canada and was an aide de camp to Edward the Duke of Kent at Quebec. Jonas wished to gain his lieutenant colonelcy in the 65th Foot, but had to transfer to the 13th Foot to achieve it, when he immediately resigned his commission, never actually serving with the 13th. Jonas retired with his large family to Ireland,[2] but the Irish Rebellion of 1798 saw him die at Three Rock Mountain in County Wexford on 30 May 1798[3].

Edward Watson began his military career, joining the 1st Battalion 9th Foot on 10 August 1808 and was rushed over to Spain to join the battalion, which was with General Sir John Moore’s army. However, arriving at Corunna, Edward was detached to form part of a military escort for a very large convoy of gold coins for the army. Their adventures, including the subsequent court martial of the second in command makes for interesting reading. He then embarked at Vigo, but soon after returning to Britain he went with the with the regiment when it sailed to Walcheren in 1809 on that ill-fated expedition, where the battalion saw no real action, but lost hundreds to the malarial fevers rife on the islands.

Whilst home on leave in Ireland, Edward received notification that the regiments was to sail for Portugal. He made his way to Portsmouth but missed his transport (although his baggage went with it) and he only caught up with it in Lisbon many weeks later. The officer that returned to his battalion was however a changed man. Whilst at home, a relative had introduced him to the rapidly expanding religion of Methodism and he returned a very serious and devout young man and was clearly now seen by many of his fellow officers as a ‘killjoy’.

This enmity, turned into ridicule from his fellow officers (he was called ‘Parson Watson’) and some serious concern was raised that the regular prayer meetings Edward held, which seem to have become very popular, even attracting soldiers in other regiments. The army was unclear how to deal with religion in the army and a number of attempts were made by senior officers to dissuade Edward from continuing in his meetings. Edward however resisted all attempts to stop him and even managed to persuade a fellow officer to join him. The matter was eventually referred to the Duke of Wellington himself, but even he (aware of Methodist meetings also in the Guards), despite his concerns regarding such influences on the troops, did not feel that he could stop the prayer meetings as long as the men still attended faithfully to their duties.

Wellington wrote to Lt General Harry Calvert from Cartaxo on 6 February 1811, requesting more chaplains to be sent out to the Army. His request had been prompted because

‘it has besides come to my knowledge that Methodism is spreading very fast in the army… Here…we want the assistance of a respectable clergyman…This is the only mode in which, in my opinion, we can touch these meetings. The meeting of soldiers in their cantonments to sing psalms, or hear a sermon read by one of their comrades, is, in the abstract, perfectly innocent; and it is a better way of spending their time than many others to which they are addicted; but it may become otherwise: and yet, till the abuse has made some progress, the commanding officer would have no knowledge of it, nor could he interfere.’

It is however clear that Edward began to be continually sent off on ‘other duties’ such as convoying wounded to hospital or French prisoners to the coast, which made it impossible for Edward to continue his evangelism.

Realising that the choice was eventually between the army or his religion, Edward resigned his commission and returned to Ireland in 1811, where he married and continued a pious life until his death at Roscommon in 1867.

Edward Watson, despite his religious conversion, which made him a very serious young man, was an excellent observer and he provides many interesting details regarding life in the army and scenes he witnessed on his travels, making his short memoir of great interest to military historians.

I do not like curtailing any memoir, but I have decided that a few passages of religious diatribe would not be of interest to a modern audience and I have removed a few such short passages, but have ensured that this has no effect on his very interesting story.

[1] Published by Ken Trotman in 2013.

[2] Having married Harriet Colclough in February 1785, they had seven children, Anne in November 1785 (exactly 9 months after the wedding); Thomas born in Montreal in 1787; Henry born in Wexford in 1789; George born in 1790; our Edward in Montreal in 1792; William born in Wexford in 1795 and Harriet born in Wexford in 1797. The Colclough’s were an Irish family based in Wexford, hence their decision to retire here.

[3] During the early days of the rising in County Wexford, an artillery company inexplicably advanced towards Wexford town without infantry support and was ambushed at Three Rocks by a large Irish force, of between one and two thousand men. Of the one hundred men with the artillery column, some 70 were killed and 18 wounded (the others presumably escaping). The losses would indicate that many were massacred, Jonas Watson died here although the precise circumstances of his death are unknown, except that we know from Edward that he marched with a relief party of militia sent to rescue the artillery column and was shot whilst on his horse.